An inevitable byproduct of tolling on I-205 and I-5 will be “toll diversion,” changes to traffic as drivers attempt to avoid paying the fees.

By Evan Watson, Jamie Parfitt, KGW TV

Published: February 13, 2024

SALEM, Ore. — As the Oregon Department of Transportation pushes ahead with plans to toll Portland-area interstates, many metro residents aren’t worried about the cost to commute alone — they’re also concerned about how tolls will affect the behavior of drivers who take these routes.

According to ODOT, the tolls will help reduce congestion on I-5 and I-205 while helping to fund roadway improvement projects. But what happens when drivers ditch the interstate to avoid those tolls and clog up surface roads?

This is called “toll diversion,” defined as a change in traveler behavior in response to pricing. Avoiding the interstate to drive on local roads isn’t the only knock-on effect, but it’s a big one. Taking public transit or carpooling could be other options.

But ODOT has said that it doesn’t have a plan for toll diversion, and officials went to state lawmakers on Friday to explain.

The presentation left state representatives and some reporters wanting more information. Consultant Matthew Woodhouse described what usually happens after tolls are implemented.

“Traffic will change and restabilize over time,” Woodhouse said. “It’s just like the first week of school. It’ll take some time for people to evaluate their travel options and choices and determine which is best for them.”

The value of a toll can depend on the anticipated travel time and other factors, Woodhouse explained. Some people may decide on a trip-by-trip basis whether to take the toll road or not — when they’re in a hurry, their time is more valuable, and they’re more likely to take the interstate and pay the toll because they want a reliable route. But when they have more flexibility to leave earlier or arrive later, it may be that they choose to take the free, longer route.

“Support for tolling tends to grow over time as people see the benefit of paying a toll for a quicker and more reliable trip,” Woodhouse continued. “You know that when you’re getting on the highway at 5:00 p.m., you’re going to be able to continue to travel at highway speeds and not get stuck in congestion.”

Right now, ODOT is looking at adding tolls on I-205 at the Abernethy Bridge, and later on at I-5 as part of a regional project. Tolling there would likely start about two years from now.

The plan is to use different toll pricing at different times of the day to reduce congestion, encouraging people to drive at off-peak hours. ODOT explained that with other toll projects, traffic dropped off significantly when tolling started, but slowly increased again in the years to follow.

Republican state Sen. Lynn Findley asked the ODOT reps to expound on that projection.

“So, what you’re saying is that diversion will be a short-lived problem?” Findley asked. “It will divert all this traffic on these side streets and impact all those, but they’ll get tired of that and pay the toll and come back. Am I oversimplifying that? But that’s what it seems like I hear you say.”

Woodhouse replied that rerouting is just “one of the many potential responses” to toll prices, and some people may just adjust the times at which they head to work or come back by a relatively small amount.

“They start going to work 30 minutes earlier or they leave work half an hour,” he said. “So ultimately, what the objective of variable pricing is to redistribute that traffic.”

Woodhouse and ODOT used data from Hampton Roads, Virginia, as an example. After tolling bridge tunnels about a decade ago, they showed how weekday traffic dropped by 20%.

“Where did the people go?” Findley asked. “Did the cars really drop by the total daily trips at those five bridges or tunnels?”

“Mr. Chair, Sen. Findley,” Woodhouse replied, “yes, there was some reduction, and we can’t say on an individual basis what happened to those trips. They left the midtown or downtown tunnel. They may have used those other alternative routes, or they may have combined their trips or made changes.”

But as it happens, KGW investigative reporter Evan Watson came to Portland two years ago from Hampton Roads, having previously reported in Norfolk, Virginia Beach and Portsmouth — right where the tolls were added.

In his experience, drivers did indeed stop taking the toll routes. That did mean more traffic on local surface roads, but it also resulted in a major economic hit for Portsmouth, the area most isolated by the tolls. After all, why would anyone go to a restaurant in Portsmouth and pay a toll to get there when they can stay closer to home or go somewhere else?

The greater Portland area could see similar impacts from the introduction of tolls — and it’s backed up by data.

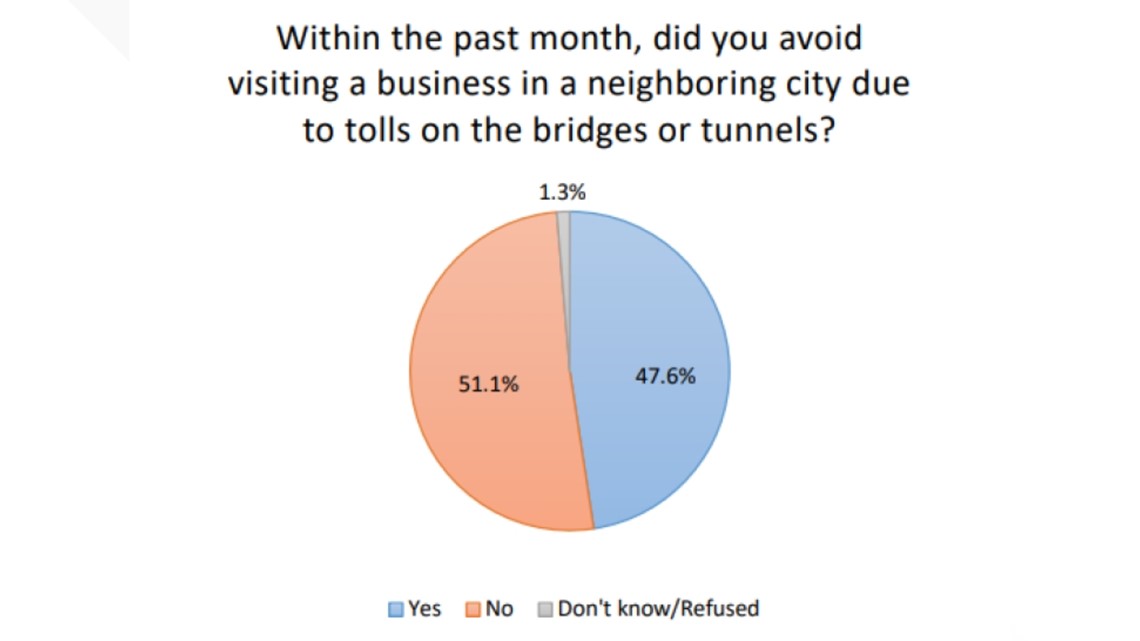

Professors at Old Dominion University in Norfolk have studied the toll impact in Hampton Roads for years, publishing multiple reports. In 2019, 47% of people surveyed said they avoided visiting a business in a neighboring city due to tolls on bridges or tunnels.

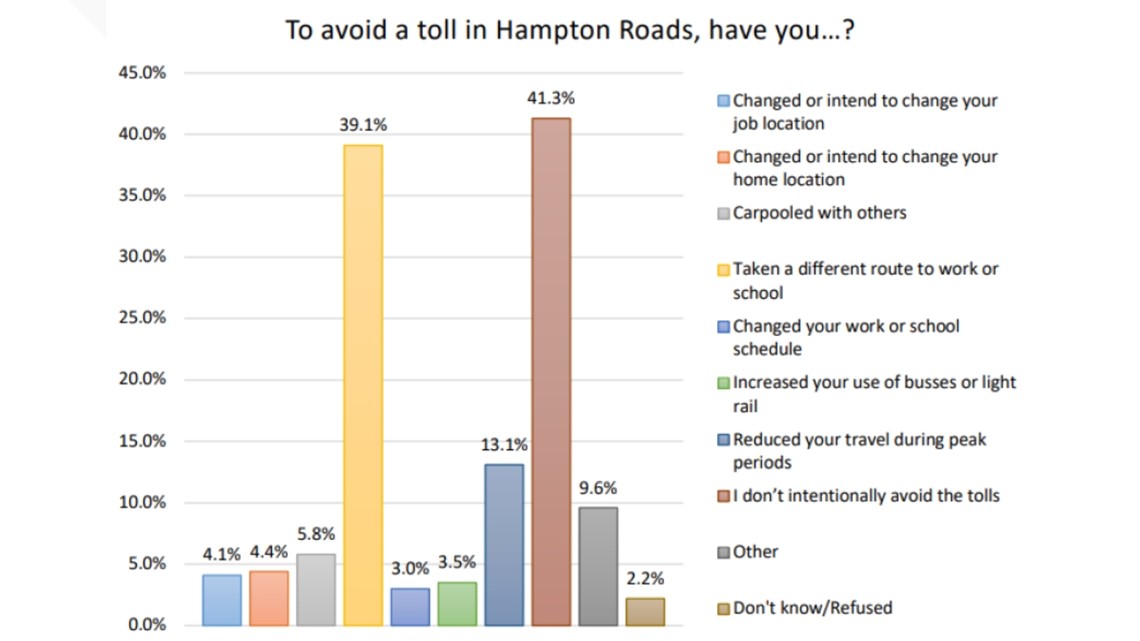

39% of people said they took a different route to work or school — local roads — and many more said they changed their schedule or changed where they want to live or work because of tolls.

In short, yes — many people “re-route” and change their driving behavior to avoid tolls, and that has lasting effects.

Democratic state Rep. Annessa Hartman, who represents a district that includes Oregon City, would see direct impacts in her district from tolling. She’s also been thinking about the example of Hampton Roads.

“I just want to say, ‘Hi, Mom,’ because she’s watching — and only reason why I say that is because she lives in Norfolk; she lives in Virginia Beach, and so, she’s sitting here texting me things that I can’t say out loud about tolls,” Hartman said. “It probably doesn’t apply to the decorum of this committee, but that traffic still really has … it’s not great. So I just had to share that.”

So what does ODOT have in mind to address this issue? They plan to model the current usage of local roads around these tolling spots, compare that to when the tolls are added, and make changes accordingly. That could mean a new traffic signal, a turn lane, reducing the toll price; Woodhouse said it would depend on how bad the problem is.

The lawmakers asked ODOT for more hard data on the alternative routes that will be most used when tolls are added.

“We’ll get a little more specific on how many trips, current capacity (when we) have that information, ditto for the Rose Quarter, thank you,” they responded.

The pricing structure could make a dramatic difference. More people will use toll roads if they’re cheap — and if they’re more expensive, they’ll find another way. There will be some programs to reduce costs for lower-income residents.

For the Midtown tunnel in Virginia, the initial toll rate in 2014 was $1.84 per car at peak time, and the governor temporarily bought that down to $1 to encourage people to still take the highway. Just ten years later, that toll rate has increased to $3.06 cents per trip, and goes up every year.