Little or no impact on road congestion or carbon emission reductions

Aug. 15, 2024

Long ago, The Onion published this famous headline next to a photo of clogged traffic in Kirkland: “Report: 98 Percent of U.S. Commuters Favor Public Transportation For Others.”

That joke contains a kernel of truth.

Many people assume transit is supposed to fix gridlock. Sound Transit’s first winning tax campaign in 1996 appealed to drivers by proclaiming “the problem is traffic congestion,” while a federal transit administrator in 2003 exaggerated the initial Seattle-Tukwila line’s benefits by comparing it to seven highway lanes. Meanwhile, opponents argued this month that Sound Transit should be held accountable for delivering “little or no impact on road congestion or carbon emission reductions.”

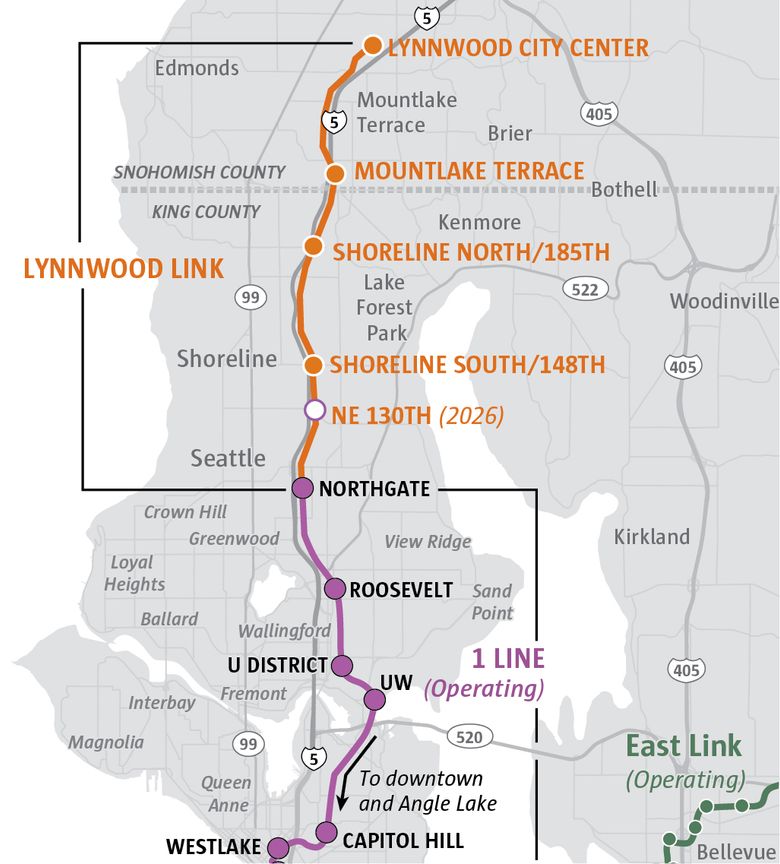

Can light rail, and especially the $3 billion Northgate-Lynnwood extension that opens Aug. 30, fix what ails adjacent Interstate 5?

Sound Transit’s new 8 ½-mile line won’t make the freeway significantly faster, partly because many customers will be former bus riders, not just former drivers. But the option for motorists to switch to trains should provide a lifeline to thousands discouraged by crushing delays. The 30% of the population who don’t drive will gain freedom to travel more often.

I-5 traffic snarls, already seeping toward Lynnwood before 2 p.m., would become worse without new rail capacity, some local experts predict. That’s especially true in 2025 and 2026, when reconstruction of worn-out I-5 decks will block three lanes in North Seattle.

Limited research exists to tell us how the new Lynnwood Link might affect congestion. Variables like new apartments, rising populations, parking fees, transit quality and the evolution of work-from-home jobs in the 2020s tilt the data.

Most of all, there’s the phenomenon of induced demand. Whenever somebody ditches their car to ride transit, someone else notices more space to drive, as if a new lane had been built. And when freeways expand, car-oriented uses develop, such as warehouse stores, isolated tracts of big homes or drive-thru eateries.

“Even though Link has done a lot in capturing trips, it doesn’t mean I-5 works better. There are more trips out there,” said Mark Hallenbeck, retired director of the Washington State Transportation Center at the University of Washington.

Congestion is roaring back post-pandemic.

Fresh data from March to June shows an average weekday trip time of 36 to 39 minutes during the morning rush from Lynnwood to Seattle and 40 to 43 minutes in afternoons, compared with 17 minutes in free-flowing traffic. Trips reach an hour during certain busy times. To be sure of arriving on time, solo drivers need to allow 90 minutes, and bus riders 60 minutes, said Roger Millar, state transportation secretary.

By contrast, light rail will cruise from Lynnwood to U District Station in 21 minutes, or to Symphony Station downtown in 33 minutes, unless there’s some blockage or outage.

A matter of scale

Even full trains can’t cure congestion because each rail line only serves as one spoke in a vast metropolitan region.

About 1.7 million households make 15.8 million trips of all kinds daily in Snohomish, King, Kitsap and Pierce counties, according to Puget Sound Regional Council surveys. The 24-mile line between Northgate and Angle Lake currently serves 78,500 passengers per day, a count the Lynnwood extension should raise to between 100,000 and 136,000, this year’s service plan says.

That’s still only 1% of regional travel.

The Sound Transit 3 tax measure, passed by voters in 2016, promised light rail to Everett, Tacoma, Issaquah, West Seattle and Ballard, three bus-rapid transit lines and more Sounder commuter train service that planners said would serve 750,000 daily passengers by the 2040s.

Even if Sound Transit meets its targets, it’s fanciful to think traffic would ebb, so long as growth and prosperity continue.

“If you’re looking at where you don’t have congestion, it’s in failed economies,” said Millar.

“There’s always going to be congestion on the highway, but if you choose not to drive yourself in an automobile, here’s an alternative that gets you where you’re going, perhaps gets you where you’re going faster,” Millar said.

Charles Prestrud, transportation analyst for the free-market Washington Policy Center, observes that light rail through Rainier Valley to SeaTac hasn’t made a perceptible dent in traffic delays, where I-5 clogs all day near Boeing Field. “Not enough people are drawn out of their cars to make a difference in crowded conditions,” he said.

Switching rides

Sound Transit’s 2024 service plan predicts 25,300 to 34,200 daily boardings in the four new stations, and if you count return trips, that’s a total clientele of roughly 50,000 to 70,000 riders, to increase by the 2030s.

Of those trips, about 30% will be new riders who wouldn’t ride existing transit, said spokesperson John Gallagher. Some will be former drivers, a market encouraged by 3,800 park-and-ride stalls. Others will be new kinds of trips, such as young adults who can ride 29 minutes to a Capitol Hill concert, half the former trip time.

Thousands of customers who transferred from buses to trains at Northgate Station, especially University of Washington students, will hop onto light rail farther north. Community Transit is overhauling its bus lines so they constantly deliver people to trains in Lynnwood and Shoreline and quit going into Seattle.